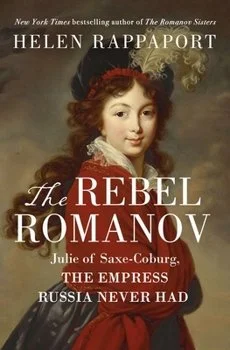

The Rebel Romanov: Julie of Saxe-Coburg, the Empress Russia Never Had Helen Rappaport (2025)

I’ve been fascinated by the Romanov dynasty ever since I read Robert K. Massie’s Nicholas and Alexandra in 1967, so I hopped on this title by the eminent historian Helen Rappaport. Juliane (Julie) of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld was a teenage German princess when, in 1795, Empress Catherine the Great summoned her and her two sisters to St Peterburg to audition to be the wife of her grandson Constantin, who was third in line for the throne of Russia. Rappaport follows Julie’s unconventional life, as she married Constantin, discovered that he was a mentally unstable brute, and fled back to western Europe, boldly creating the life she wanted. Julie’s story is meticulously documented from original letters and documents of the period, and the photo section of this biography is especially rich.

Here are brief recaps of a couple of my other reviews of biographies of women:

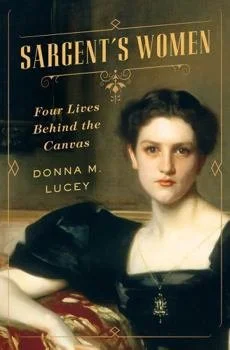

Sargent’s Women: Four Lives Behind the Canvas Donna M. Lucey (2017)

If you like Gilded Age gossip, this is a multi-biography that you may want to read. I thought it would be focused primarily John Singer Sargent’s relationship with four of his female subjects, whose portraits are widely known and reproduced: Elsie Palmer, Sally Fairchild, Elizabeth Chanler, and Isabella Stewart Gardner. (That’s Elizabeth Chanler on the cover of the book.) Sargent painted portraits of these wealthy American women between 1888 and 1922, but in fact his contact with them outside his professional role was fairly limited. So . . . what this book does offer is a view into the excesses that the upper classes indulged in during a period of American industrial expansion and political corruption. My favorite section was the one on Isabella Stewart Gardner, whose private art collection became the famed art museum in Boston that bears her name.

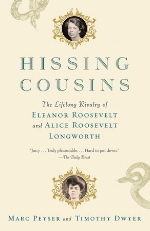

Hissing Cousins: The Untold Story of Eleanor Roosevelt and Alice Roosevelt Longworth Marc Peyser and Timothy Dwyer (2015)

This dual biography of Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962) and Alice Roosevelt Longworth (1884-1980) reveals many family secrets. Alice, the daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt, lived in the White House in her youth and became the celebrated “Princess Alice.” Eleanor was Theodore’s niece, who married her distant cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt and herself moved into the White House as First Lady during his presidency. Although Alice and Eleanor played together as children and saw each other socially throughout their lives, they differed radically in their political beliefs and in their personalities. Alice was a Republican, flamboyant, sharp-tongued, and dedicated to influencing the course of history through back-door methods. Eleanor was a Democrat, introverted and slower to speak, but she was a reliable sounding board for FDR on many issues, and she found a strong public voice in advocating for civil rights nationally and human rights internationally. Though the biographers veer into cattiness occasionally, Hissing Cousins is a lively addition to the history of the American Century. Alice and Eleanor are presented as flawed but brilliant women who made their marks in the halls of power.